When is a £19billion global conglomorate an SME?

When the government wants to pretend it's buying more from British small businesses

In 2015, Matt Hancock claimed the government would spend £1 in every £3 with Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) by 2020. The government failed to meet that target.

But, as I outlined in the main post in this series, that's not for a lack of trying.

Sadly, I don't mean trying to procure more from SMEs, I mean trying really hard to make the statistics appear as if it were. A much easier task.

One of the areas it has tried to help itself along has been in the definition of what an SME actually is.

That should be pretty straightforward. The Companies Act 2006 (as amended) defines small enterprises in Section 382, and medium enterprises in section 465. The definition of medium is what interests us, as it sets the upper bounds of the whole SME definition.

To be a medium enterprise, a company must meet any two of these requirements:

- Not than 250 staff

- Turnover not more than £36m

- Balance sheet total not more than £18m

Section 467 then sets out further exclusions from being considered as a medium-sized company (and therefore has the purpose of excluding from the overall definition of SME). It states that company is ineligible to be treated as medium-sized if (1a) it is 'a public company' or (1c) ‘a member of an ineligible group’.

So, that's pretty clear, right? A company must be privately owned, and if it's owned by another company the entire group must be eligible to be defined as an SME. And the whole entity being evaluated must meet two of the size requirements above.

On that basis, if global giant IBM set up or acquired a subsidiary in the UK called 'Blue Dudes', it wouldn't be eligible to have it counted as an SME, however many people there wore t-shirts, because it'd be a group company of IBM, which is ineligible. I think that's hard to argue with, and seems pretty sensible.

So, now we know what an SME is and isn't, let's take a look at a month of data on how government procures from SMEs on the Digital Marketplace (the place where procurement on the Digital Outcomes and Specialists framework happens).

A month on the Digital Marketplace

I picked, with no prior view of the data on supplier awards, a recent month that had seen reasonable procurement activity and for which the dates for the 'work must start by' had passed, so it would be reasonable to expect the contracts to be up on Contracts Finder.

In this month there were 53 procurements listed on the Digital Marketplace's Outcomes lot. Of those, only 16 (at the time of writing) had contract details uploaded, so there was information about the successful bidder. (I'll write a separate post about declining transparency on the Marketplace.)

These 16 contracts totalled just over £16m of spend (though the contract values varied widely.)

4 of the contracts, together worth just over £10m, were declared as being awarded to large companies. That left 12 contracts, worth just under £6m, being declared as going to SMEs.

That's just under 37% of (published) spend going to SMEs, which is above the government's target of 33%. But with digital being the ideal industry to buy from SMEs, compared say to aircraft carriers, I'd have expected this to be higher still for government to stand a chance of meeting the target overall.

Sadly, even that 37% figure turns out to be a mirage.

I checked the provenance of all 12 'SME' contract awardees. I found 5 of them were actually either subsidiaries of large groups or publicly-listed companies, which excludes them from meeting the criteria for SME status.

One of the companies is owned (via a chain of 6 holding companies) by a global conglomorate worth £19bn, yet is reported in the government's figures as an SME.

Sadly, the UK government has form here, having previously listed the UK subsidiary of AWS, yes, AWS the global infrastructure division of Amazon, as an SME.

What's more, in this month in question, it was these Large-but-reported-as-SME companies which had been awarded the larger contracts, taking almost two-thirds of the listed SME spend.

Moving these contracts from the SME category to the Large category to properly reflect their status, means the spend for this month was adjusted, from declared to actual, as follows:

| Total Spend | SME Spend | SME % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Declared | £16,067,097 | £5,877,177 | 36.58% | |

| Actual | £16,067,097 | £2,004,052 | 12.47% |

So, in reality, only 12.5% of spend on the Digital Marketplace in this month (from the data published), was with genuine SMEs.

Note: I'm deliberately not stating the month the data are from, or giving identifying data about any of the supplier companies, because this is not about calling them out. They haven't done anything wrong, and are good companies. There is also no doubt raised about whether the contracts should have been awarded to them. The buyers did nothing wrong, and these suppliers are perfectly able to fulfil the contracts. This is purely about how government chooses to categorise SMEs and report the data in order to appear to meet targets.

Some reasons why

So how could nearly half of the contract awards listed as being to SMEs be incorrectly categorised as such?

The government has made it very clear it wants to be able to announce that the proportion of spend going to SMEs is going up — but without changing any actual policies or behaviours, there's only one other way to make that (at least appear to) happen: fudge the figures.

Studies have found time and again that if senior leaders set targets and demands teams show they are meeting them, the rest of the organisation almost unconsciously 'games' them without meaning to carry out any fraud — it's just human nature to try to please superiors. There's probably at least a hint of that in dozens of tiny ways, plus a good dash of political pressure. Nobody individually really does anything very wrong, but somehow the organisation collectively has gamed the numbers.

But here are two other things that are factors …

The UK government actually uses the EU definition for SMEs rather than its own

Now, we all know how keen the UK government has become on adopting EU rules to override UK legislation, so here's the latest example. Rather than use the SME definition in the UK's Companies Act, the UK government uses the EU definition (page 5, point 2 of that NAO report), which it has continued with after Brexit.

This could well make sense, unifying things with our largest trading partners, even if not actually updating our own legislation to reflect the new position.

So let's look at the EU definition of an SME. The first definition from the EU was in 1996, but the modern definitive document is the Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises which was then adopted in 2007 into Commission Regulation (EC) No 70/2001 of 12 January 2001 on the application of Articles 87 and 88 of the EC Treaty to State aid to small and medium-sized enterprises. It appears that this was a bit too wordy for the Treasury to take it all in, so they just picked a bit out of it.

But the European Union have very helpfully provided a public-facing, easy to read User Guide to the SME definition too, which really won't melt your brain, and I would recommend it to the Treasury and CCS.

And it turns out that in defining the term, the EU was mindful of the need for 'Measures to prevent abuse of the definition':

"One of the main objectives of the new definition is to ensure that support measures are granted only to those enterprises which genuinely need them. It is important to stress that the definition contains several anti-circumvention measures designed to reserve the advantages of SME support programmes to real SMEs. In this respect, the simplified approach of the present guide must not be used to justify artificial corporate architecture aimed at by-passing the definition."

'Artificial corporate architecture' such as a chain of 6 holding companies between a global conglomorate worth £19bn and an 'SME'? Why yes.

The EU definition of an SME places a lot of importance on establishing that an SME is 'autonomous', and not controlled by non-qualifying enterprises, or that the linked enterprises don't together exceed the definition. It uses the guide of 25% or more of the ownership of the enterprise being controlled by another enterprise. (There's quite a bit more to the rules than that, but that's the simplest I can make it for a blog post.)

So, it turns out that the EU SME definition isn't too far away from the definition in the Companies Act 2006, just with different numbers against the criteria. There is still the requirement to consider ownership, and whether an entire group of companies qualifies, rather than the single entity.

Whether it's the UK definition or the EU definition of SME, all 5 of the businesses I identified as being mis-reported as SMEs would still be excluded from being defined as SMEs. So it makes no difference to my findings here that CCS uses the EU definition.

CCS gets companies to self-declare with incomplete information

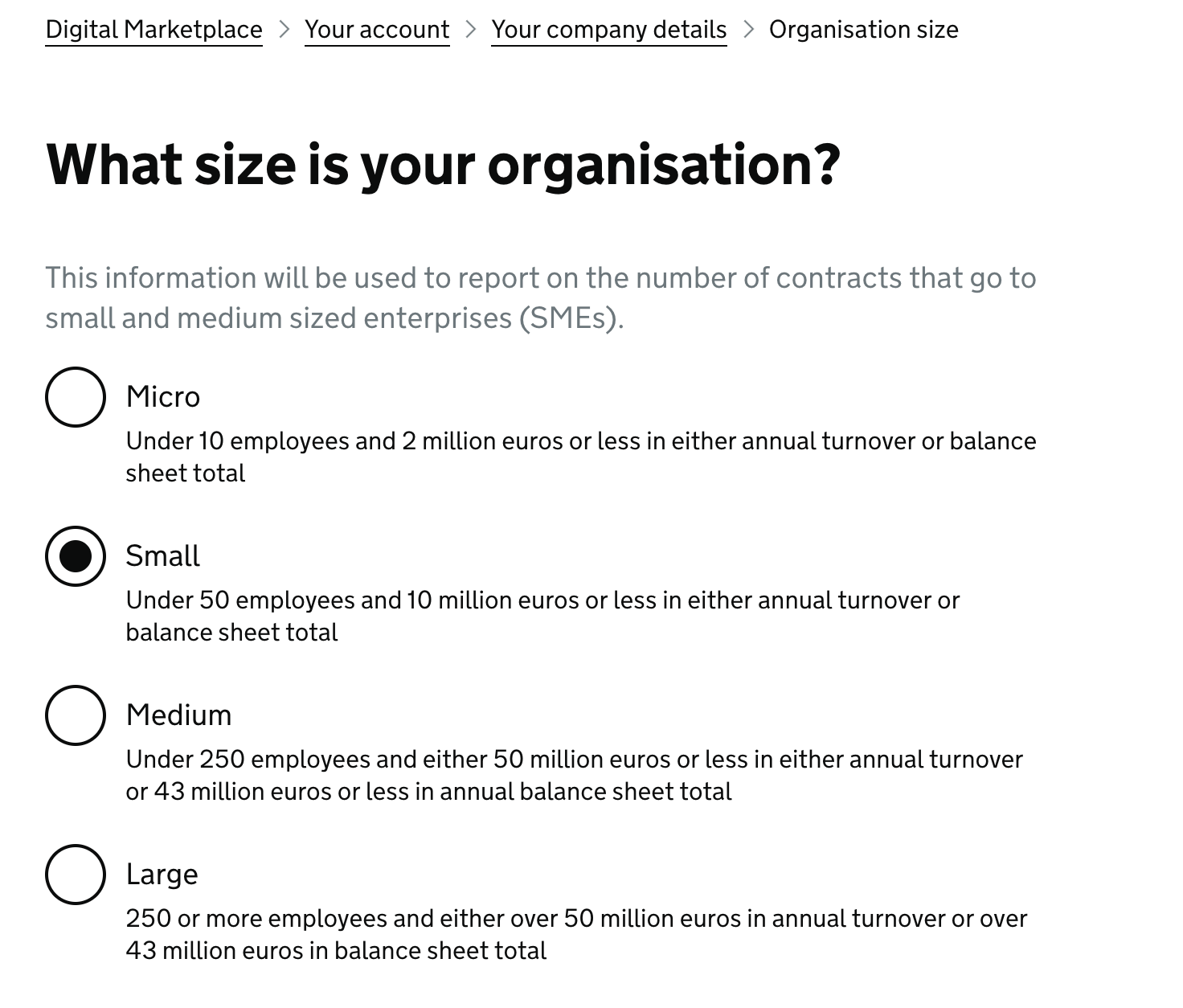

It then turns out that the decision about whether a supplier is categorised as an SME or not in the procurement data is left to the suppliers, on a form in the Digital Marketplace.

But the content design on the form they need to fill in is based only on a partial use of the EU definition above:

The emphasis is on 'your organisation' too, not any concept of 'groups' or parent companies, or other ownership restrictions. So it stretches the definition of SME as broadly as possible.

That means that suppliers who aren't classed as SMEs under the UK or even the EU definition could perfectly reasonably answer this question in a way they believe is accurate — and in doing so end up helping the government appear to achieve its SME spend targets.

But there's more …

Clearly, taking one random month from within the last 12 months on the digital marketplace isn't statistically valid, so let's look to take another sampling from different published data on government spend with SMEs.

In 2017, because the government couldn't crow about spend with SMEs increasing towards the target in the 2015–16 period (because it went down), they did a PR exercise trumpeting their top 100 SME suppliers.

Given we have some doubts about which suppliers government records as being SMEs, let's give the list a little double check, shall we?

For our sampling, I checked services offered by all the companies on the list, to select those that offer services that could be reasonably listed on G-Cloud or DOS frameworks, as that's the sector we're focusing on. That produced a list of 6 companies — remember, all 6 should be SMEs by either the UK definition or the EU definition.

As before, I'm not going to name the companies, because they have done nothing wrong and are good companies. This is only about government labelling them as SMEs in order to claim credit for working with small businesses.

I checked the published accounts for each company for the 2015–16 period, as well as ownership information.

2 companies out of the 6 are very clearly SMEs. 1 company on the list is questionable as an SME under ownership rules because of having more than 25% controlled by a large private equity firm, but we'll give the benefit of the doubt (the small print of the EU definition allows this ownership to be discounted if it's a financial investment only and doesn't take control, e.g. appointing directors — and we can't know that from the outside) so we will still count it as an SME. 1 company has turnover in excess of the UK definition, but beneath the EU definition, so we'll also count that as an SME given the use of the EU definition by CCS.

That leaves 2 companies out of a sampling of 6, chosen only by sector, that clearly did not meet either the UK or EU definitions of SME for the period in question. One even had a turnover of £130m!

So, in order to appear that it's making progress towards its target of spending £1 in £3 with SMEs, the government has released supporting data in which 1 in 3 listed suppliers (from our sector) were not actually SMEs.

Conclusion: a significant proportion of the government's claimed spend with SMEs is not actually spent with SMEs

We've taken two views on two different releases of data, and in both cases we've found multiple instances of government reporting spend with large suppliers as being spend with SME suppliers.

This is falsely giving a rosy picture of how much government is working with SMEs.

How can we fix this?

- The UK government should have a single definition of SME, and update the definition in the Companies Act if they wish to keep using the EU definition.

- All government references to SMEs must be based on the same definition.

- Until there's a single definition, all data releases, or other publications or announcements, relating to SMEs from the entire public sector should specify the definition of the term that is being used, in full. This definition should be the same as used at the point of data-gathering.

- CCS should update the self-declaration form to include the full requirements of being defined as an SME, including not being part of a group that doesn't meet the qualifications or is a public company. It can't use a partial version that helps improve the stats.

- CCS should then require all listed suppliers to check and update their status against the more detailed criteria.

- CCS should consider automating the identification and flagging of cases where they may need to check the status of suppliers. They already gather suppliers' Dun & Bradstreet numbers, and D&B holds the necessary data.

Public Sector Procurement in 2021 — Blog Box Set

In the rest of the series we'll explore some of the issues raised in more depth, including digging into the data — and look towards some solutions.

To be notified of new posts, either subscribe to our email newsletter (sign up in the footer at the bottom of this page), or follow us on Twitter at @convivio.

The articles published so far in this series are:

- The problems with public sector procurement in 2021

- A brief history of government promises to work with SMEs

- Latest data shows government spend with SMEs continues to fall

- When is a £19billion global conglomorate not an SME? (this article)

About Convivio

Convivio is a challenger consultancy, helping knowledge-work organisations be more effective in the digital age.

Credits

Edited by Joe Baker.