Healthy Governance 3: understanding stakeholders

Any new approach to governance needs to meet the needs and expectations of stakeholders. What do they actually think?

In the previous post we came to a workable definition of governance. Now we’re going to look at those who do the governing. What are their needs?

We tend to know the ‘wants’ they express — reports, presentations, spreadsheets, assurances, targets. But we don’t tend to dig into the needs behind these, and ask if there are other ways to serve those needs. We just assume that they accurately express the wants that would best serve their needs.

In reality, I’d suggest that stakeholders are no different to any other group of human beings at being able to know how best to serve their needs in a context that is not their specialism. They have no superpowers that make them better than users, but we would not just take a user saying ‘I need a spreadsheet showing x’ and instantly build the spreadsheet. We would dig into the underlying needs and see if there are simpler, better ways to serve them.

Teams are often cowed by the authority of stakeholders, without really understanding them or thinking about the human needs behind their instructions or requests. That is, in my view, a major contributory factor to friction between them.

Before we move on with developing healthier governance for digital projects — let’s take some time to think about stakeholders as people with needs to be served.

Listening To Stakeholders

Over the last couple of years I’ve taken every opportunity I can to listen to senior stakeholders of digital projects talk about their work. I also listened to a variety of people in senior roles within digital delivery teams, across a range of projects, speaking about their stakeholders and governance.

This hasn’t been formal user research. Sometimes I got an hour to dig into the deeper stuff — but sometimes I just got ten minutes over coffee at a conference to pick someone’s brains on a few basic points. So this is just a start. In time I hope to expand this with the help of my professional user research colleagues. But let’s start with good enough, and move to perfect later. Our governance approach should be designed for iteration as we learn more.

If you’re a stakeholder who would be happy to take part in a confidential user research interview to ensure your own needs are factored into the Healthy Governance project, please email me: steve.parks@convivio.com.

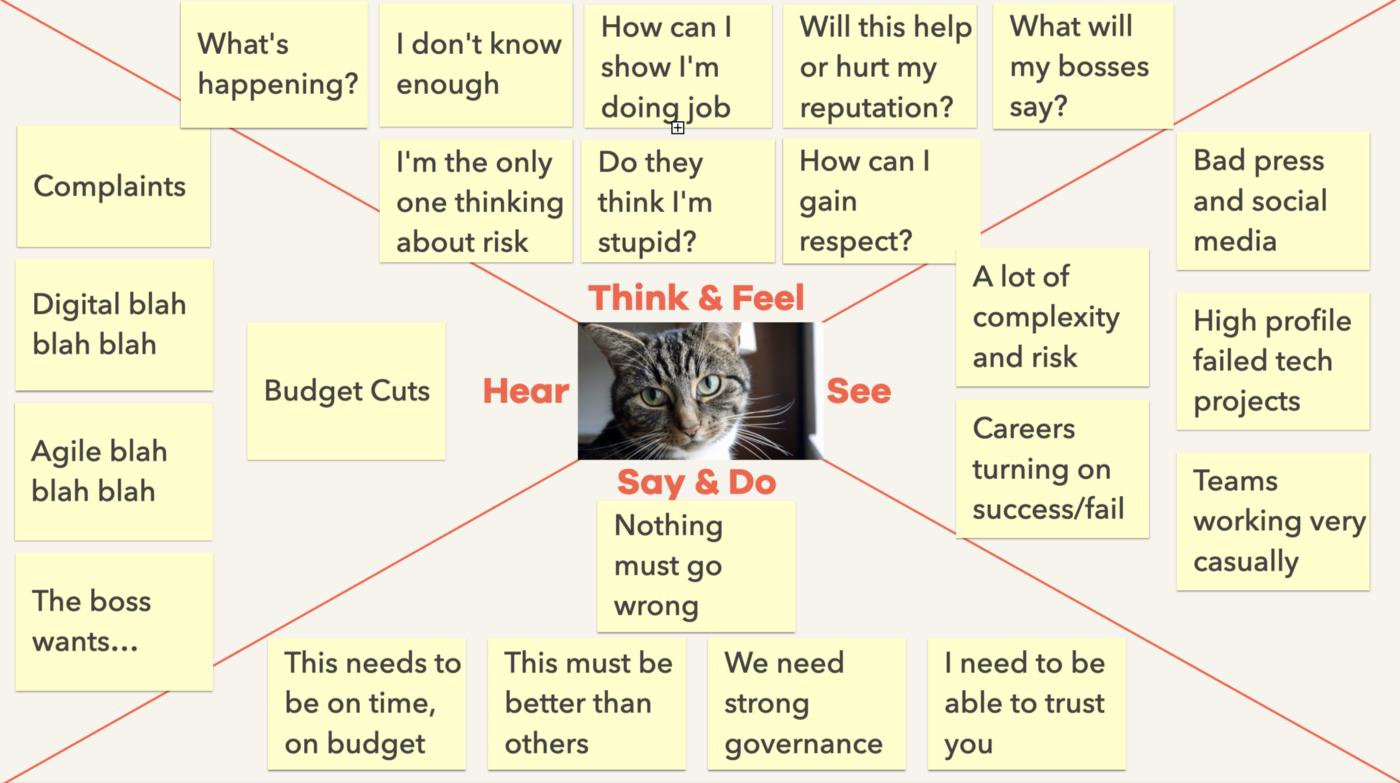

Empathy Mapping

To help with sifting my notes from these conversations I used a simple empathy map. This is divided into four quadrants, representing what stakeholders hear, see, think & feel, and say & do.

On this, I used sticky notes to capture common issues I heard raised across a number of conversations.

What stakeholders hear

Stakeholders often refer to hearing complaints from all sides. From other parts of the organisation who depend on some of the output from the digital team (“They think they always know best”, “They don’t deliver what we tell them to”, “They don’t understand the pressures at the sharp end of the business”) and from the digital team themselves (“People tell us what to do rather than involving us in solving problems”, “All their requests are last minute urgent ones, they never plan ahead”), or from the senior management (“Everyone’s working in silos”, “Why don’t we have X yet?”, “Why hasn’t my idea happened”) and so on.

Next, many talked about jargon overload. A whole load associated with ‘digital’ — UX, devops, cloud, and so on. Lots of word soup, but what does it all actually do? Why is it good? Then the word ‘agile’ being used like a magic wand — “We haven’t got a project plan document, we’re using Agile” and so on. Not in the least reassuring. Agile is too often used as a one word excuse for not doing any of the things stakeholders expect to see, without showing them what reassurance they will get instead.

Stakeholders also often get something landed on them from above (everyone has an ‘above’). It’s often passed on without context or opportunity to question or steer, just being told “The boss wants…”

And finally, nearly everyone refers to regular budget pressures in some form or other — “We need to do more with less.” Depressingly, some organisations have captured the word ‘Agile’ to use in the context of budget cuts — Agile working means hot-desking at fewer desks, or making do with fewer staff — underlining the need for us to better explain what we mean by 'being agile', or to avoid the term completely and just explain how we will work in smaller parcels of work to reduce risk, increase learning and speed up delivery.

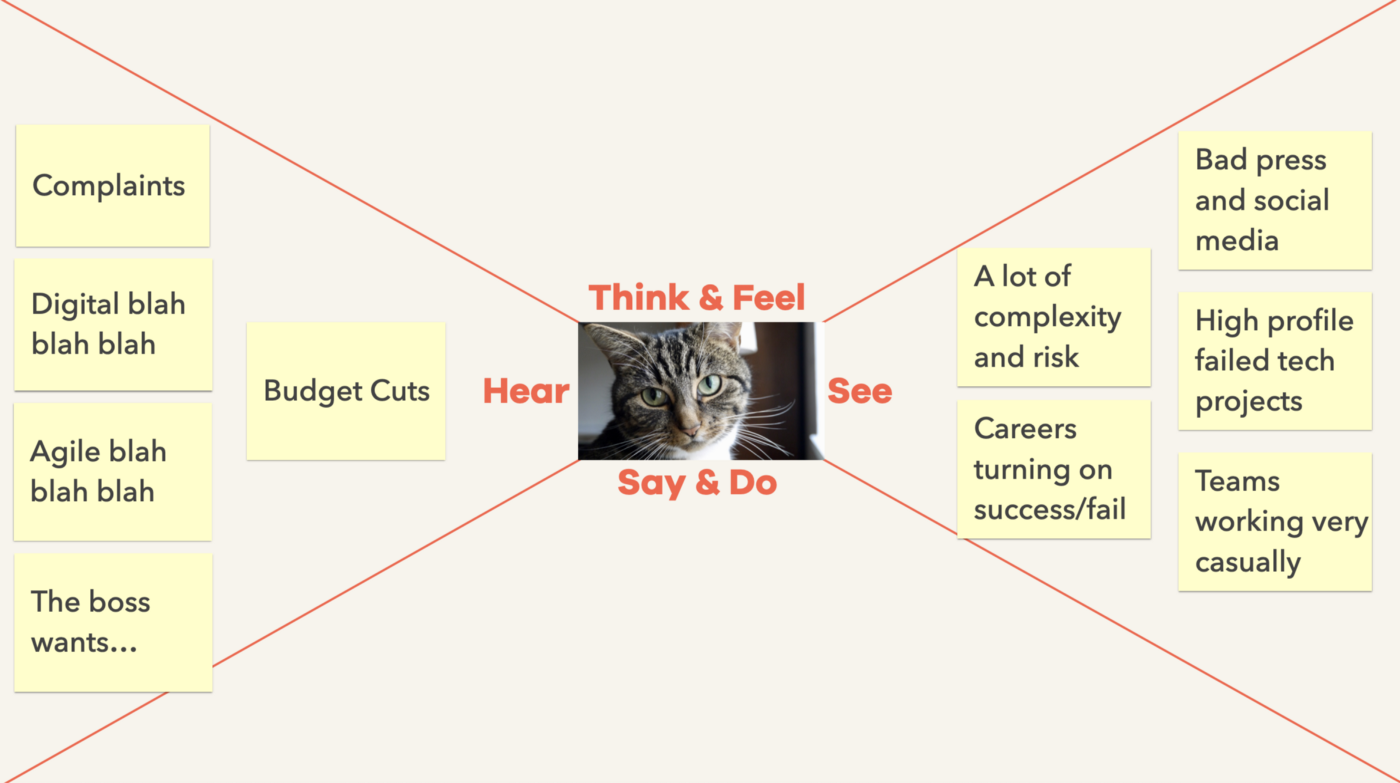

What stakeholders see

These things that stakeholders hear and see, lead them to think they’re the only one thinking seriously about the risks.

They feel trapped between not knowing enough about the project and what is going on, and needing to show their own colleagues and superiors that they are doing a good job.

They’re worried about how this project and its outcome might affect their reputation. They worry about what their own boss will say about the project.

But at the same time, I was surprised to find some insecurity. Some people expressed a worry that the project teams would think they were stupid because they didn’t understand all the technology, or about Agile, or all these new ways of working. They wanted to earn the respect of their team too.

So the thread running through this is feeling trapped between a traditional organisation and its formal ways of working, and a digital team and their very informal ways of working.

What stakeholders say and do

Finally, these thoughts and feelings lead stakeholders to say and do the things that teams see and hear.

Some of this is aimed at getting the team to take the risks seriously, and avoid problems arising. In an abscense of understanding about the reaility of risks and their impact, and how agile approaches help with managing risk, it becomes ‘nothing must go wrong’, and if even small things go wrong it creates a worry that they might be the tip of the iceberg. That leads to a doubling down on the position with ‘this must never happen again.’

There’s an attempt to lock in all the expectations of the organisation, from the regular promises they have to make in high level meetings, so that a defined thing gets delivered on time and on budget. That’s simply the way organisations measure delivery being successful.

In an effort to help ensure this delivery and remove risks they try to put in place what they believe are strong governance processes. These are of course based on how they’ve seen things done in the past, and the expectations of reports placed on them from above. It may also be based on things they’ve learned on management courses and in books in the past. They haven’t designed these processes for their purposes, they generally all report doing what is seen as best practice, and what they feel is expected of them. It’s a set of traditions. Nobody seemed to be particularly satisfied these processes were solving the problems, but they weren’t going to get into trouble for doing them.

And they are very aware the project and their work will be compared with others. Whether this is genuine competitors in the market, or just competition between departments or teams — they want to do things that will get noticed. They want what is delivered and the way it is seen to be done to be perceived as better than others. They are looking for the upside to the risk. What could make them, their team, department or organisation look really good, and maybe even earn some fame?

What‘s missing?

Reflecting on the empathy map, I note that a lot of the focus of stakeholders is on the direct pressures they get from above and below them — leading them to feel squeezed. There’s not a lot of chance to look to the horizon, or think strategically. There’s also not a lot of chance to think about what long-term value looks like, let alone how to provide it.

And when value is discussed, it’s often a proxy for the cost of goal-achievement rather than the true value provided to users and the organisation.

This is not because stakeholders don’t want to be able to think in these ways. If prompted, they dream of being able to focus on such things.

So that gives us an opportunity: how can we help make the day-to-day grind of them satisfying the basics of their role more streamlined to provide time and attention to focus on bigger things?

The special fear of digital projects

I want to take a moment to reflect on some of the comments I heard that showed an underlying fear or worry from the stakeholders.

It’s hard enough keeping up with technology and digital ways of working (and let’s be honest, industry fashions) when you work in digital all day — but as a stakeholder, it’s impossible. Their work requires them to pay attention across a whole range of organisational functions.

So there’s a tendency for digital projects to be just seen as magic.

Magic sounds fun in a Harry Potter sense, but when you’re a stakeholder it brings a fair bit of fear. Not being able to understand how something works is scary, when your organisation (and therefore your career) critically depends it.

I’ve even heard stakeholders ask for a ‘magic button’ in their digital systems to get to an outcome. The word magic is used to joke away the fact that they have no idea how it would work in practice, and are a bit scared about the whole thing.

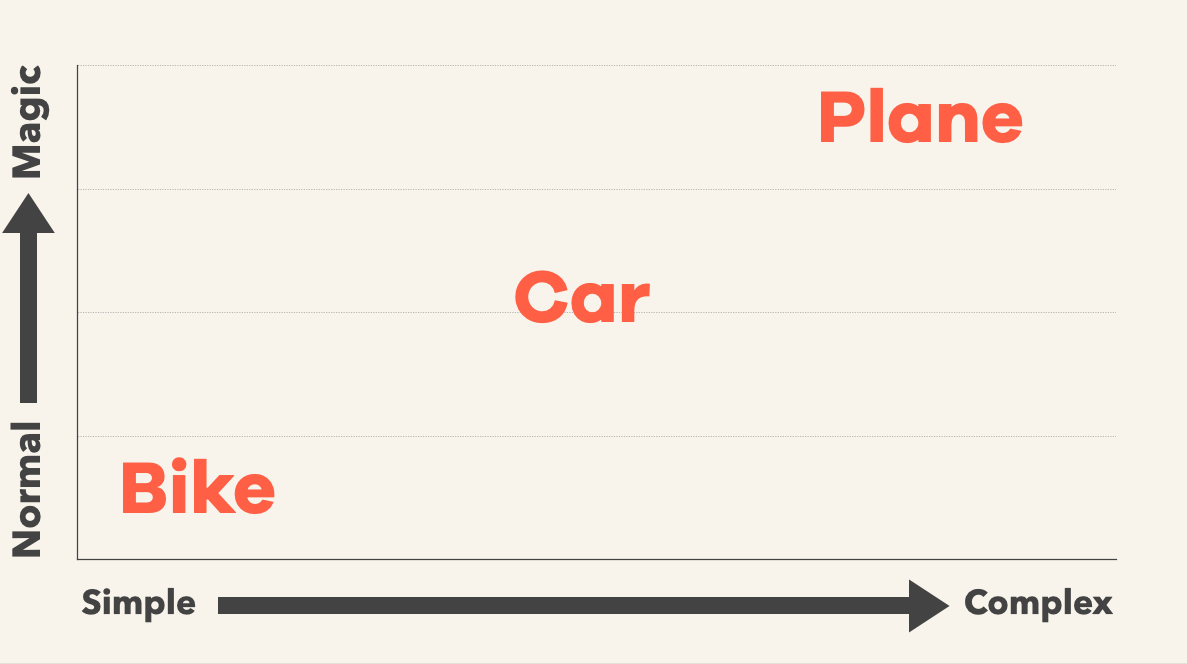

Let’s think about what impact that has on people. If we think about modes of transport, for example, and map three of them on a chart reflecting level of complexity, and perception of magic, it’d look something like this:

We can all understand exactly how a bike works. We can see the pedals turning the chain, turning the wheel — and we understand the concept of balance ever since being toddlers. Most of us would be happy to do simple repairs on a bike, or at least we’d understand what the bike shop staff are talking about. This means bikes seem normal to us. We don’t have any fear or worry about this technology.

With cars, many of us can drive, and we can understand how it all works pretty well — the steering, brakes, accelerator, gears. We can read the dials. Most of us don’t know the ins and outs of the details, and get someone else to check and repair our cars — but we understand roughly what happens under the bonnet. It’s a middling level of magic, and our fear and worry is middling too.

But with a plane, we don’t really know where to begin. We’ve learned the broad outline in physics at school, but one look in a cockpit at all the switches and dials and we couldn’t begin to make sense of what it’s all for. What impact does changing the flaps control lever have? It’s highly technologically complex to an average person, so it rates fairly highly on the perceived ‘magic’ scale too. For many people, there’s quite a lot of anxiety at travelling by plane. Even seasoned travellers, if they’re honest, will admit to a little bit of trepidation at take-off, landing in windy weather, when the seat-belt lights click on mid-flight, or when there’s an announcement over the tannoy asking if anyone on board is a pilot and didn’t have the fish for dinner.

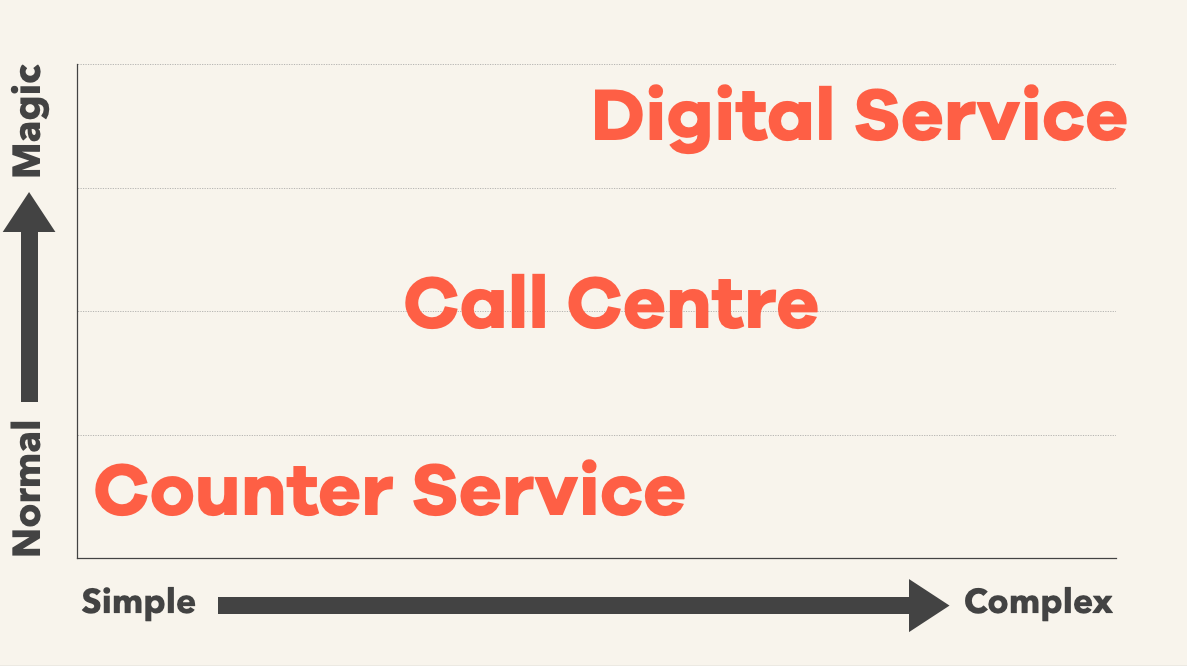

So let’s think about how this concept of complex=magic looks for a stakeholder in an organisation providing services that need interaction with members of the public…

Everyone can understand what it takes to make a counter service work roughly okay and not blow up. You need a room, some desks, some staff and probably a lot of forms. There’ll be problems but a competent manager can figure them out and gradually improve the processes. The fear is low from stakeholders.

A call centre gets a bit more complicated because you have advanced phone systems to deal with on top of the processes. Average managers don’t know how they work or how to fix them, but they know that the phone company can come and fiddle about in the room in the basement and get it working again pretty swiftly. It is complicated, but it’s not complex. The fear is middling.

With a digital service, however, most stakeholders simply don’t know how it works. How do you get lots of webservers to all run the software together so it can handle lots of people? How do you stop people hacking into them? How do you manage them when you don’t even really know where they are? And what about all those lines of code — how do you begin to understand how they all work? Then what is UX? And so on, and so on. For most stakeholders, flying a digital service is roughly like travelling by plane. You have no doubt everybody is smart and will do their jobs well — but if, just if, there is one mistake, it could be catastrophic. And what about hackers, the press, and so on. It's complex. The fear is high.

So we need to be mindful of that fear as a result of the magic of technology. We need to think about stakeholders in meetings, gripping the armrests at takeoff or when they perceive the fasten seatbelts sign is being switched on, and consider how we can provide information and data in ways that inform and reassure them, giving them some feeling that everything is genuinely under control.

Stakeholder Needs

So, from all of this, we can draft a set of user needs for our stakeholders:

- I need to understand what the project is going to deliver for the organisation and the users, and how it is progressing towards that, so that I can set expectations and justify investment.

- I need to understand what might go wrong with the project, and the impact that might have, and how these risks are being managed, so that I can feel confident to give the team freedom and report effectively to the organisation.

- I need to know what resources are needed and what constraints exist so that I can balance the needs of different teams within the organisation, and help everyone succeed by unblocking any problems.

- I need to see whether the team is working healthily together, and being effective, so that I can support them in resolving any issues and doing work that the organisation needs, in ways it can be proud of.

We can then use these in designing our healthy governance approach.

If we can serve these needs better, it frees up stakeholders to be more positively involved. If these needs aren’t being served, they will request more intensive traditional forms of governance.

Wrapping up

Hopefully we now feel we understand stakeholders a little more, and what their needs are from the governance of digital projects.

Maybe you could even try an empathy mapping exercise with your specific stakeholders. If you don’t think you can interview them, try to put yourself in their shoes and consider what they might be seeing, hearing, thinking & feeling, and how that leads to what they say and do.

What are their underlying needs behind the wants they express?

In the next part of this series we’ll look at what the team’s needs from governance are.

Coming Up

In the coming weeks, I’ll publish the following blog posts in this series:

- The mission

- What is governance for?

- Understanding stakeholders (this post)

- Understanding teams

- Maximising value

- Reducing risk

- People, time, money and resources

- Behaviours, practices and safety

- Assurance

- Continuous Improvement

- Implementation and next steps

To follow along, either subscribe to the Convivio newsletter, down in the footer of this page, or follow us on twitter at @convivio where we’ll announce each new post.

If you want to discuss with me or send ideas, feedback, or anything except abuse, I’m on Twitter as @steveparks. DMs are open for anything you can’t say in public, or you can email me at steve.parks@convivio.com.

And I’d be very grateful if you spread the word to other geeks like us, interested in good governance of public sector digital services. Thanks!

Main photo of somebody standing by a remote lake in heavy snow holding a brightly coloured umbrella, by Anastasia Yılmaz

This post was originally published on our Medium blog at https://blog.weareconvivio.com/is-it-a-larger-cow-or-has-it-just-been-moved-closer-65d5a7b364b0