Pandemic Aftershocks / Leading an agency in a time of high inflation (pt. 1)

Inflation around the globe is escalating quickly.

The first canary in the proverbial coal mine that there's serious trouble ahead may just have been announced — Netflix has lost subscribers for the first time in a decade.

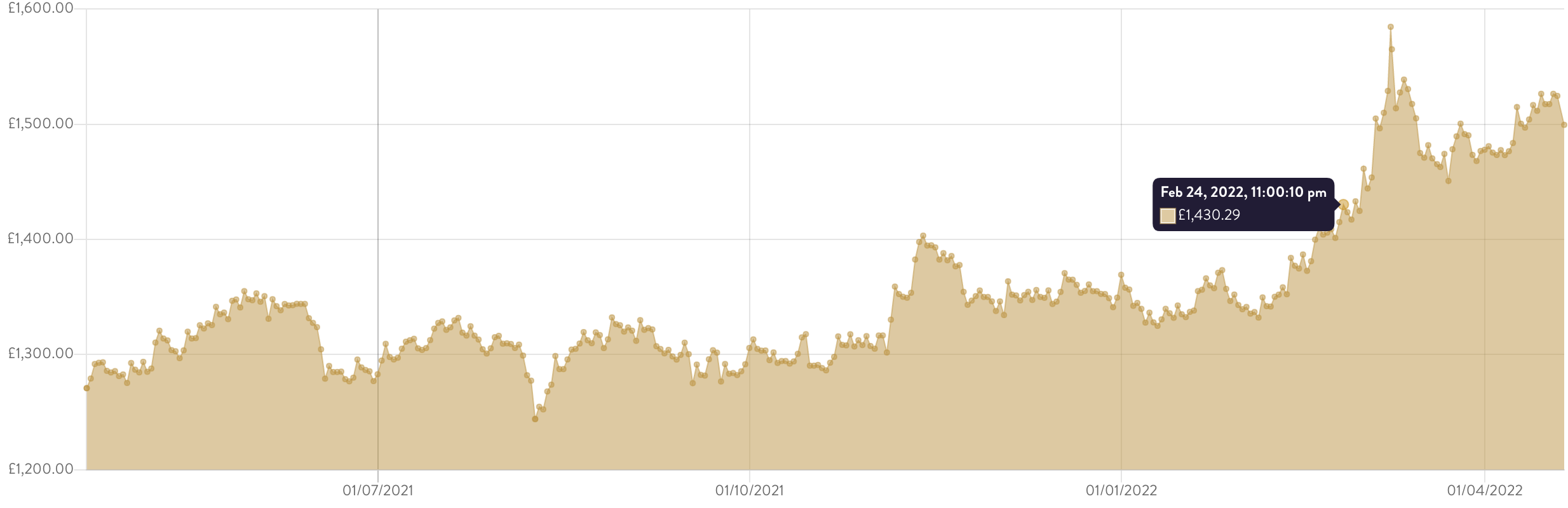

A further sign of the direction of travel can be see in the trends in investments. The price of gold — classically, a safe-haven in times of financial turbulence — began increasing in early February, and then jumped further in the weeks following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February.

Rates of inflation in North America (US; Canada), Europe (Eurozone; Germany; France; UK; Sweden) and elsewhere (Australia; China; Singapore; India; South Africa) are all moving substantially upwards, triggering central banks and finance ministers to take actions in countries across the world.

Although the macroeconomic actions taken will be different in each national context, and the effect and experience will differ substantially as well, the economies of the world are more interconnected now than they've ever been. What hurts in one national economy will be felt many others — it's a problematic global fragility that we'll explore in a future post.

That means that, in all likelihood, the world is on the brink of an era of high inflation.

We highlighted this in the Radar Report for 2021, under the 'Pandemic Aftershocks' theme.

Inflationary impacts compound the cost-of-living crisis

This is especially worrying for employees, as inflation is outpacing wage growth — in the UK, the US, Canada, Europe and elsewhere.

Prices for fuel, food and consumer goods are all increasing, and without wages keeping pace, agency staff will quickly begin to feel the impacts of high inflation.

This is why inflation is hated by all of us — by wager-earners (agency staff), by wage-payers (agency owners and leaders) and by policy-makers, alike. When wages don't keep up with the prices of the stuff they need to buy, people get poorer. That’s the case even if the inflation being experienced is mostly in food and fuel — the two things have got more expensive due to the long tail of the pandemic and, as we discussed previously, that are getting more expensive due to the Ukraine war and the sanctions on Russia — rather than the ‘core inflation’ factors (goods and services other than food and energy) that are considered in monetary and fiscal policy-making decisions.

Is a recession on the horizon?

Governments across the world have responded to these pressures in a series of ways.

First came the stimulus packages of mid-2021 that were intended to revive businesses that had been paused or stagnating during the first 18-months of the pandemic. These packages saw the beginning of many healthcare protections being rolled back to facilitate the 'return to work', but in turn creating further economic and social turbulence from the fertile petri dish that enabled new coronavirus variants and infection surges.

Economic stimulus packages, though, need to be wielded very carefully. Whilst they can create momentum where there would be stagnation otherwise (think of the New Deal response to the Great Depression), the stimulus itself can mask what's really going on and, when withdrawn, especially if too early or too quickly, have devastating detrimental effects — especially if inflation means prices are rising while wages remain essentially static.

Second has been a series of delays in action. There's been talk of inflation concerns in the long tail of the pandemic for the best part of the last year, but as with the US Fed's and Bank of England's comparatively sluggish actions in the 1970s, delay by central banks and policy makers now has allowed inflation to begin to spiral.

These delays make the shocks bigger — the escalation of the economic emergency, and then the required remedial action.

Third, though, actually balancing all the necessary activities is exceptionally difficult, and, despite the willingness, it's not clear that anyone is really getting that balance right at the moment.

All in all, the risk of recession on both sides of the Atlantic is now very high.

This is completely new for virtually all agencies … and most agency leaders, too

I was discussing with an agency leader very recently, a member of the Agency Senate, what this means for agencies.

In most of the world, inflation has been essentially stable now for a very long time, she said, longer than many agency leaders' experiences stretch.

Rates across the globe have been less than 5%, and often much lower, for most of the last 30 years, since the early 1990s. In places, current inflation rates have not been seen for more than 40 years, since the aftermath of the oil crises of the 1970s.

That's longer than virtually all agency businesses have been around, we noted.

There are a few agencies in the Senate that have been around for 25 years or more, but not many at all. A small number agency leaders have experience in the top levels of business that stretches back to the early 1990s, even fewer to the late '80s, and just a handful to the early '80s.

A huge proportion of agencies are less than a decade old and, in their current form, didn't even experience the 2007–08 banking crisis.

That experience gap, this Senator pointed out, could be very problematic in the likely era of high inflation ahead. As much as policy makers, agency leaders will need to learn, most for the first time, the painful lessons of the 1970s.

Smart agency leaders will take some immediate steps to plan and prepare for the era of high inflation that's ahead of us.

What can agency leaders do?

In the face of these giant national- and global-scale issues, it's very easy to feel insignificant, impotent or even despondent as you try to navigate a safe route through for your team, your business and yourself.

There is no need to despair, though.

As my friend in the Agency Senate said very pointedly, being able to talk and learn from others is important in situations like this — from agency and business leaders who have experienced this before, and also by taking the small-but-vital time needed to learn the lessons from previous eras of high interest, such as the 1970s.

In part 2 of this blog, we'll look at specific and highly-practical actions that agency leaders can take.

If you want a sneak preview of the kinds of things we'll be discussing, you may like to take at the actions in my previous blog, about the pressure on food prices arising from the war in Ukraine. But, in part 2, we'll take a thorough-going and practical look at ways that agency leaders can respond to safeguard those that they're responsible for: the business and the team.